Sneak Peek of the Mapping Issue!

Thank you to the backers of Conveyor Magazine’s Kickstarter project! We are so appreciative of the support that we thought we ought to give you , we thought we’d share a small sampling of the images and text included in the upcoming Mapping Issue.

Project Series takes a look at Sarah Anne Johnson’s “Arctic Wonderland” …

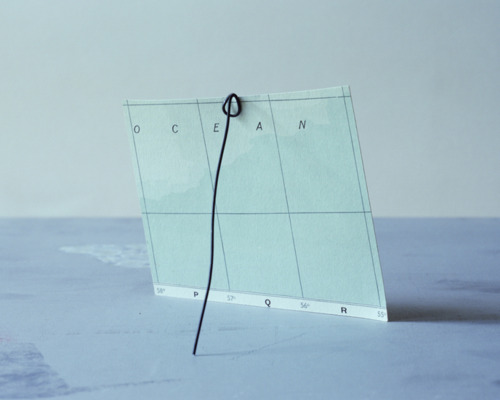

Today, the Arctic is a combination of shifting icescapes and a cartography of International laws, which parcel out limited economic zones to five surrounding countries, leaving the middle as an open territory. Johnson explores how these zones define progress, possession, and preservation in a geopolitical world. - CM

Black Box, 2010.

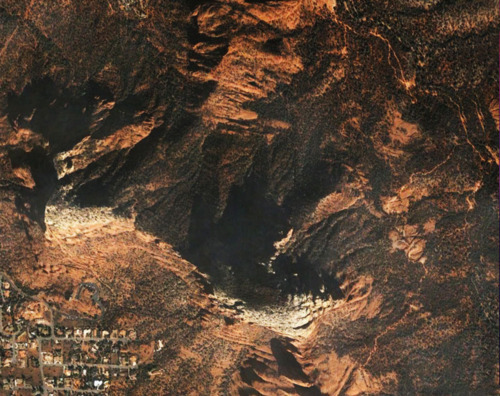

… and the comprehensive “Mason-Dixon Survey” project by Colin Stearns.

The Mason-Dixon Line has held a near mythical place in the American psyche since its charting in the 1760s. While it has grown into an intangible cultural division between North and South, it began as a pragmatic solution to a land dispute and was marked by highly physical traces. - CM

A few from the Group Show - curated from a free & open call for submission:

John Mann

Dierdre Donohue

Mary Mattingly

The Artist Feature looks at the images and writings of Peter Happel Christian…

Many cartographers and photographers aim to produce consumable images that add to our understanding of the world. What exists beyond the borders of a map or the frame of a photograph is absent from the slipstream of pictures and lost to history and recollection.

And a little Lori Nix…

Ok. No more spoilers! The Mapping Issue goes to press in just one week!

We couldn’t be more excited! However, we still have a a ways to go to reach our goal! Help us keep the momentum going, by spreading the word through conversation, blogs, facebook, email and more!

Just 20 Days Left to Back our Kickstarter project! Help us reach our goal :)

{ http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/conveyor/conveyor-magazine }

Field Notes

Conveyor editor Sylvia Hardy examines Ley Lines, the inspiration and namesake of Alexandra Lethbridge’s most recent project. She also speaks with archeologist Dr. Michael Frachetti to learn more about how Ley Lines function in contemporary geography. Read more below:

Last week, photographer Alexandra Lethbridge flew east to France, while I headed west towards the Sierra Nevada mountains. While our paths took us in opposite directions, we were able to connect via email to discuss Ley Lines, a term coined by the British amateur archaeologist Alfred Watkins in the early 1920’s to describe invisible lines believed to create areas of magnified energy that either derives from or results in the alignment of topographical features and sacred buildings. In an ongoing project, Lethbridge uses Ley Line maps to direct her journeys and then documents her experience on photographic film.

According to Lethbridge, photography is the perfect medium for capturing the residues of heightened energy. “I have solely been using film photography out of an interest to see if the concentrated energy will affect the film – which it has,” Lethbridge says, “Some photographs have the power to move people while in their presence, leaving a residue with whoever views them in some form or another.”

Although energy connected to changes in magnetic fields is a subjective experience that cannot be proven scientifically, there are reasons archaeologists look at culturally settled landscapes for edifices that create patterns from an aerial perspective. These points are often architectural structures.

I spoke with Dr. Michael Frachetti, archaeologist and director for Spatial Analysis, Interpretation and Exploration lab at Washington University in St. Louis. Frachetti specializes in spatial analysis and archaeological landscape modeling using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and remote sensing.

Frachetti has never used the term Ley Line to discuss anything in his research, but he is aware of the Ley Line hypothesis. In archaeology, he uses and creates maps to look for alignments between human-made structures. Once a pattern is found, he analyses what the motivation behind it might have been.

Meaning can be present in an active or habitual convention,” Frachetti explains, “Humans are building the landscape in both practical and spiritual ways. Sometimes they build-in meaning very passively” and other times with more consideration. “Linearity may serve a function—and sometimes it just looks better. Whether the meaning behind the patterns is an environmental or social convention—it is probably somewhere in between.”

When I asked Frachetti whether he thought Ley Lines ultimately amounted to the arrangement of objects in a straight line, or line of sight, he said that today landscape architects, surveyors and GIS give line of sight a lot of credit.

“Ley Lines may very well be related to a line of sight but not every line of sight can be conceived of as a Ley Line,” Frachetti tells me, “The issue of Ley Line is, is it an active creation? Or is it a result? It seems to be more of a metaphysical thing…do those rocks form a path, and is that important?”

Frachetti offers a set of mosques on the island of Jerba, Tunisia as an example of structures that had been formed by reference to something other than their visual alignment. Although the mosques form a line of sight, they were actually aligned because of their acoustics. The project maps the “soundscape” of the Muslim call to prayer to investigate the development of social and geographical boundaries associated with the establishment of mosques over the last 1200 years.

Visibility and invisibility can both be important, Frachetti explains, and some alignments are supposed to be seen and some are supposed to be hidden. Frachetti uses a number of tools to discover the relationship between the structures he studies. In his on going research in Kazakhstan, he used Google maps to find major alignments in burial sites.

Both Lethbridge and Frachetti are searching for points in the landscape to draw a line, points that have been embedded with many years of natural and cultural changes. A line in its simplest form, Frachetti reminds me, is made by connecting two dots. In mapping, the importance often becomes which two points you choose to draw a line between.

Alexandra Lethbridge: {www.alexandralethbridge.com}

Dr. Michael Frachetti: {www.anthropology.artsci.wustl.edu/frachetti_michael}

GIS at the SAIE Lab: {www.saie.wustl.edu/gis-4.html}

6 Sep 2011 / 2 notes / Alexandra Lethbridge Geography Ley Lines Mapping Sylvia Hardy Field Notes