Field Notes: Marfa, Texas

Last weekend, Conveyor Editor Sylvia Hardy traveled down to Marfa, Texas for The Chinati Foundation’s 25th Anniversary Weekend, which was celebrated with special exhibitions by Hiroshi Sugimoto and Jean Arp. Here she looks at new work by Sugimoto and Bettina Landgrebe and reviews an exhibition opening for the Chianti Foundation’s current Artist in Residence, Justin Almquist.

Despite the fact that everything in Marfa, Texas looks like an art installation or a stage set—think neighboring “Untitled, Prada Marfa” 2007 by Elmgreen and Dragset and the film Paris, Texas by Wim Wenders—this past weekend, the odds that you were actually driving by an art installation were extremely high.

Hiroshi Sugimoto

Hiroshi Sugimoto used this opportunity to show work from his new Pagoda series; sculptures made from optical glass and photographic film. While the seascape is a well known motif in Sugimoto’s photography, this exhibition features seascapes set into optical glass within the part of a pagoda traditionally used to house the Buddha’s ashes or other sacred relics. The works’ small size was out of character for Sugimoto. He joked that if he could not match the largeness of Donald Judd’s sculptures, he would compete through a created sense of intimacy and fragility. Judd’s sculptural works inspired Sugimoto when he emerged as a conceptual artist in the 1970s. Asked whether his new pagoda works reach the artistic level of Judd’s concrete works, which are permanently installed on the Chinati grounds, Sugimoto replied, “That is for the viewer to decide.”

Justin Almquist

The Chinati Foundation’s current Artist in Residence, Justin Almquist, is a native Texan with a BFA from Pratt and an MFA from the Munich Academy of Fine Arts.

His exhibition titled You don’t have to scratch me to get meat opened at the Locker Plant on Saturday night, and was labeled around town as “punk rock art.” His papier-mâché sculptures and pen and ink drawings, which frequently merge into watercolor paintings, had a lot of humor and animal references. There is also something deeply childlike in the work, especially in his skull hats and in his imaginative drawings of bottom feeders. Almquist says he emphasizes these creatures, because he doesn’t think they get enough credit.

The exhibition opening was refreshing and lively, featuring performances by local punk rock groups, the Solid Waste and Foundation for Jammable Resources. It was a typically West Texan musical and aesthetic entwinement of punk rock and hard country.

Bettina Landgrebe

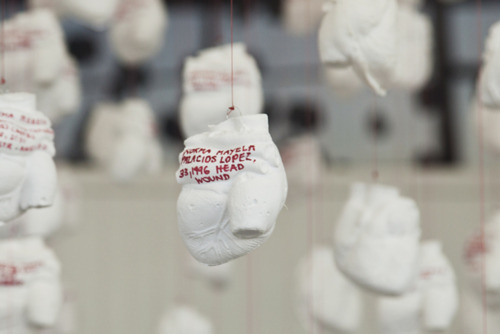

Unexpectedly, Bettina Landgrebe took a more direct political tone with her installation Beaten With a Hammer. Each time I drove passed Big Bend Coffee Roasters, no matter what time of day, I couldn’t help but gaze at the mysterious constellation of objects suspended from the ceiling. Finally, I got out of the car and saw the work close up. The constellation fell away to a mass of individual plaster hearts, each inscribed with the name, age, date and method of death of a woman killed in Juárez, Mexico. A city just a couple hours drive from Marfa. Landgrebe states that the “476 hearts are testimony to this war… It is not a war contained amongst warriors, but it is a war that devours life and replaces it with human greed and the vanity of power. The physical and psychological warfare perpetrated against women is a testament to this naked disregard for life after war.” In this installation, Landgrebe gives many pieces of information, but what she leaves for the viewer to decide is the “Why?,” especially the “Why” of “Why is there no international outcry?”

The day after I saw Beaten With a Hammer, I was able to visit with a friend in El Paso. One morning we walked over the pedestrian bridge to Juárez. It was a jarring experience (especially after having just seen Bettina’s piece), but one that I hope helps me further figure out the “Why?”

Bettina Landgrebe is a conservator at Chinati.

For more of Bettina Landgrebe’s work: { http://bettinalandgrebe.com/home.html }

For More About the Chianti Foundation: { http://www.chinati.org }

18 Oct 2011 / 3 notes / Donald Judd Marfa Sugimoto Sylvia Hardy Field Notes

Happenings: Pingyao International Photography Festival

This week, Conveyor Editors Sylvia Hardy, Maria Sprowls and Alison Chen landed in Beijing. They caught a connecting flight to Taiyuan and drove to the ancient city of Pingyao for the Pingyao International Photography Festival.

Since arriving last week, we have made our way around the ancient city mostly by bicycle. On Tuesday, September 21, 2011 we celebrated the opening of the Pingyao festival. The week started rainy and gray, but, on the morning of the festival, blue skies broke open and filled with fireworks, confetti and hang gliders. The festival’s exhibiting photographers paraded down a red carpet towards the city gate as Mongolian music, drums rolls and voices in song illuminated their procession. Most of us had never experienced such an exuberant celebration in the name of photography. The festival exhibits over 20,000 photographic works in the same town. They bridge art with fashion, bring together emerging and well-known artists, and build a space where East meets West.

To further define the festival, we asked some of the artists participating in the exhibitions to share their thoughts on the city of Pingyao and it’s International Photography festival. Below are some of their images and thoughts:

“The festival is a celebration of art. Our prints were crafted, printed and framed in a building on site, all funded by the Shanxi province.”

“It is an amazing production, as we witness frames being constructed and walls being built at amazing speeds — exhibitions are constructed out of air.”

”A beautiful example of the human spirit.”

…

Stay tuned for more from the Pingyao International Photography festival!

23 Sep 2011 / 0 notes / Alison Chen Maria Sprowls PIP Pingyao Sylvia Hardy Happenings China

Project Series: Maria Sprowls

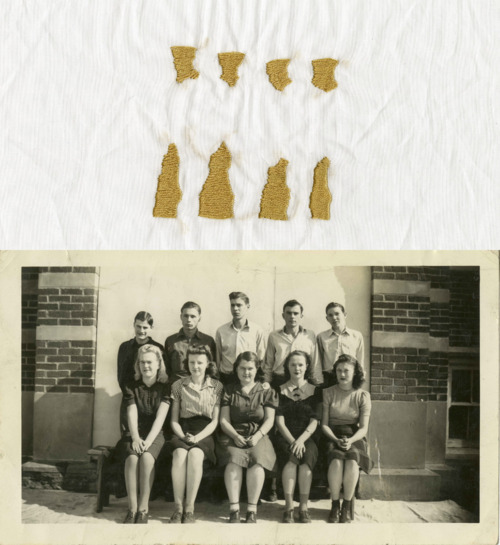

In the series Found Women, artist Maria Sprowls traces the ethereal social bonds that women maintain. Combining found photographs circa the early 20th century with feminine hued stitching, a second portrait emerges; one in which the fading image remains vibrant.

The distance or absence of a human body may make the space between each one of us appear devoid of content or physicality; however, Maria sees this space as a dwelling for memories of the past and the desire for the present. In this world, the sensitive and strong emotions of companionship and bonding become a delicate archipelago.

12 Sep 2011 / 2 notes / Found Photography Maps Sylvia Hardy Maria Sprowls Project Series

Field Notes

Conveyor editor Sylvia Hardy examines Ley Lines, the inspiration and namesake of Alexandra Lethbridge’s most recent project. She also speaks with archeologist Dr. Michael Frachetti to learn more about how Ley Lines function in contemporary geography. Read more below:

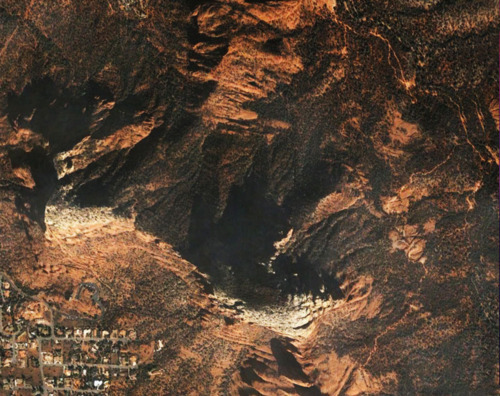

Last week, photographer Alexandra Lethbridge flew east to France, while I headed west towards the Sierra Nevada mountains. While our paths took us in opposite directions, we were able to connect via email to discuss Ley Lines, a term coined by the British amateur archaeologist Alfred Watkins in the early 1920’s to describe invisible lines believed to create areas of magnified energy that either derives from or results in the alignment of topographical features and sacred buildings. In an ongoing project, Lethbridge uses Ley Line maps to direct her journeys and then documents her experience on photographic film.

According to Lethbridge, photography is the perfect medium for capturing the residues of heightened energy. “I have solely been using film photography out of an interest to see if the concentrated energy will affect the film – which it has,” Lethbridge says, “Some photographs have the power to move people while in their presence, leaving a residue with whoever views them in some form or another.”

Although energy connected to changes in magnetic fields is a subjective experience that cannot be proven scientifically, there are reasons archaeologists look at culturally settled landscapes for edifices that create patterns from an aerial perspective. These points are often architectural structures.

I spoke with Dr. Michael Frachetti, archaeologist and director for Spatial Analysis, Interpretation and Exploration lab at Washington University in St. Louis. Frachetti specializes in spatial analysis and archaeological landscape modeling using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and remote sensing.

Frachetti has never used the term Ley Line to discuss anything in his research, but he is aware of the Ley Line hypothesis. In archaeology, he uses and creates maps to look for alignments between human-made structures. Once a pattern is found, he analyses what the motivation behind it might have been.

Meaning can be present in an active or habitual convention,” Frachetti explains, “Humans are building the landscape in both practical and spiritual ways. Sometimes they build-in meaning very passively” and other times with more consideration. “Linearity may serve a function—and sometimes it just looks better. Whether the meaning behind the patterns is an environmental or social convention—it is probably somewhere in between.”

When I asked Frachetti whether he thought Ley Lines ultimately amounted to the arrangement of objects in a straight line, or line of sight, he said that today landscape architects, surveyors and GIS give line of sight a lot of credit.

“Ley Lines may very well be related to a line of sight but not every line of sight can be conceived of as a Ley Line,” Frachetti tells me, “The issue of Ley Line is, is it an active creation? Or is it a result? It seems to be more of a metaphysical thing…do those rocks form a path, and is that important?”

Frachetti offers a set of mosques on the island of Jerba, Tunisia as an example of structures that had been formed by reference to something other than their visual alignment. Although the mosques form a line of sight, they were actually aligned because of their acoustics. The project maps the “soundscape” of the Muslim call to prayer to investigate the development of social and geographical boundaries associated with the establishment of mosques over the last 1200 years.

Visibility and invisibility can both be important, Frachetti explains, and some alignments are supposed to be seen and some are supposed to be hidden. Frachetti uses a number of tools to discover the relationship between the structures he studies. In his on going research in Kazakhstan, he used Google maps to find major alignments in burial sites.

Both Lethbridge and Frachetti are searching for points in the landscape to draw a line, points that have been embedded with many years of natural and cultural changes. A line in its simplest form, Frachetti reminds me, is made by connecting two dots. In mapping, the importance often becomes which two points you choose to draw a line between.

Alexandra Lethbridge: {www.alexandralethbridge.com}

Dr. Michael Frachetti: {www.anthropology.artsci.wustl.edu/frachetti_michael}

GIS at the SAIE Lab: {www.saie.wustl.edu/gis-4.html}